On Mark Mahaney’s Polar Night

British Journal of Photography

March 2020

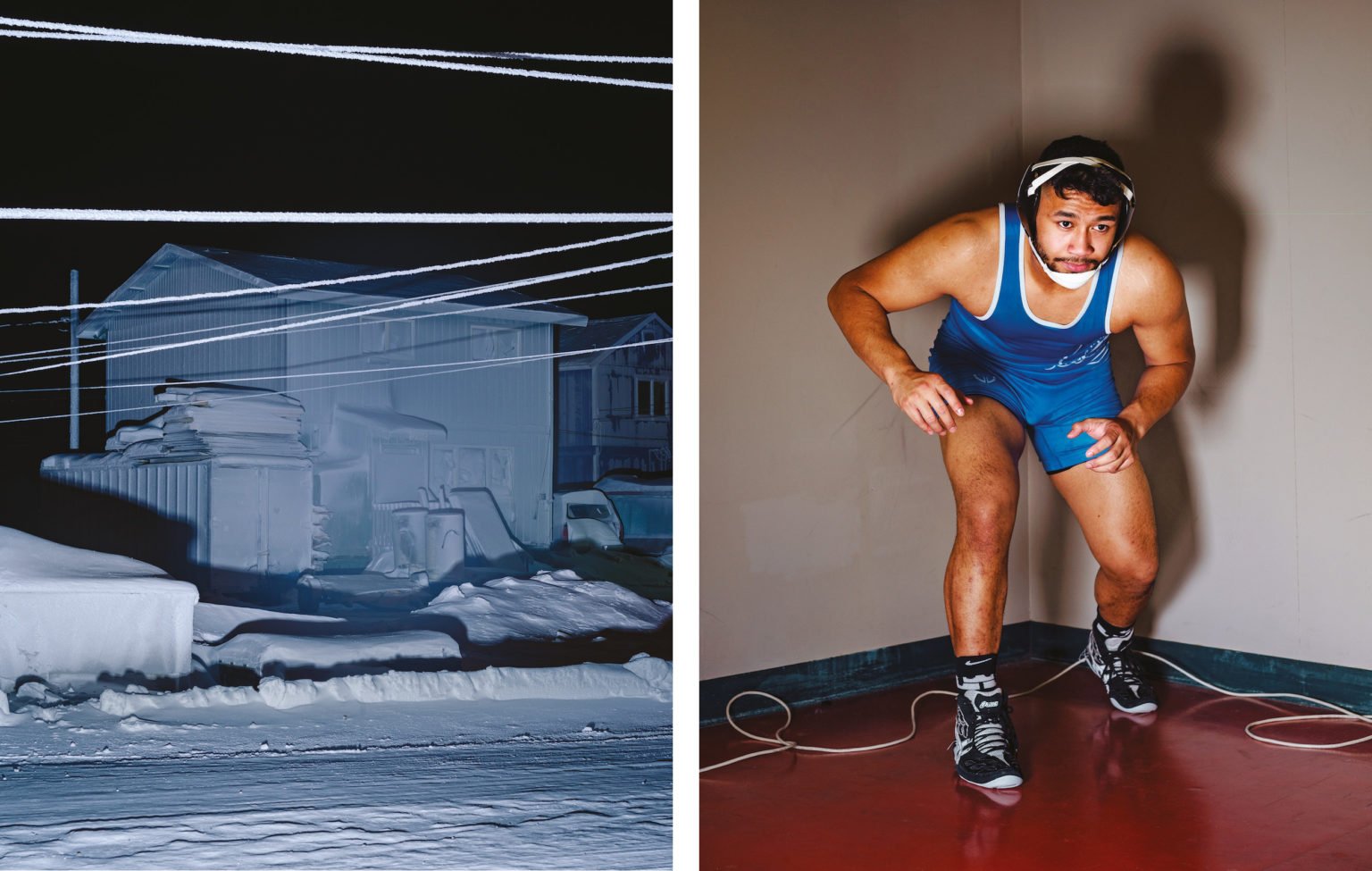

Mark Mahaney, from the series Polar Night © Mark Mahaney

“Many photographic projects I respect involve these long, romantic road trips,” Mark Mahaney explains as we sit across from each other. “But those types of projects didn’t feel within reach between working nonstop and my role as a husband and father.” For the last decade, he has developed a respected career as an editorial and commercial photographer, regularly commissioned by magazines such as The New Yorker, Time, and Vanity Fair and companies like Airbnb, IBM, and Nike. In recent years, he had grown hungry for something he could pursue outside his day job. One day, he serendipitously read something that piqued his interest. “I saw this headline for a town that experiences ‘polar night’—when darkness lasts for more than 24 straight hours—for 65 consecutive days every year. I was immediately hooked by the idea and the fact that this place has been deemed ground zero for climate change.” The project also seemed logistically tenable. Mahaney lays it out step by step. “I go to this place. I don’t quite know what the project will be until I get there. And then I fly out the day the sun comes up and I’m done. There were these natural bookends that aligned with what I was looking for in a personal project.” With that, he began to research and prepare for a trip to Utqiagvik[1], Alaska, the northernmost city in the United States located 300 miles above the Arctic Circle.

Mahaney did significant research about how to photograph in arctic conditions; the average low in Utqiagvik is –20°F. “People reported back with these horror stories,” he tells me. “I knew I would have to shoot digital because film might crack under these conditions. And I ended up bringing two of every piece of equipment so that I was covered if something happened, like condensation ruining a camera or lens because we moved too quickly indoors from the outside.” He also had to figure out how to physically make pictures while bundled in layers, with goggles often fogged by condensation, and gloveless hands viable for only a few seconds at a time.

When Mahaney finally made it to Utqiagvik, “it felt like we were landing on the moon,” he remembers. “I thought it was going to be a ‘day in the life’ kind of project where I would document the culture of this place through portraits, landscapes, pictures inside people’s homes.” But finding subjects to photograph proved more difficult than anticipated. “People are in hibernation mode,” Mahaney explains. “And it also felt wrong for a white guy to come into this native community, ‘cold’ knocking on doors to make portraits; I didn’t want the project to feel exploitative.” Utqiagvik is home to approximately 4,500 people, 60% of whom are the indigenous Inupiat. “I knew if I didn’t change course in some way, I was going to walk away with nothing.”

I’ve been so captivated by Mahaney’s stories that I’ve barely registered the monograph in front of me. I run my hand across the cover, an imageless softback with POLAR NIGHT in white. On the table between us, the book appears black until I open the cover to reveal true black end pages. I flip back and forth a few times, admiring the subtle shift between a midnight blue and black. Mahaney interjects, “the cover is based on the color of the sky while I was there.”

Polar Night feels like wandering through an otherworldly, almost apocalyptic landscape. There is an overwhelming sense of disorientation as one flips through Mahaney’s concise edit of just 26 pictures, a feeling heightened by his use of both bleak black-and-white and surreal color photographs. “Because it’s a small project, I wanted there to be some push and pull. I didn’t want it to be single note. So, I varied my aesthetic approach throughout, just like I do with assignment work.” Throughout our conversation, he repeatedly acknowledges the role his commercial background has played in this—his first—personal project. “Some things are lit by flash, others are naturally lit. Some pictures are more action-filled, others are still, quiet moments. Some are black-and-white, others are color.”

I pause at the first picture, attempting to decipher the scale of his subject matter, which I know is snow, but could just as easily masquerade as a sand dune in another context. A few pages later, a striking black-and-white of a snow-plowed path, as if lit from a car’s headlight, appears to lead off into nothingness, complete blackness. Looking closely, I notice a lone cross, barely peeking out from the snow, along the road’s edge in the distance. “It’s hard on the mind, body, and spirit to live in this town,” tells Mahaney. “Darkness brings darkness. Crime, suicide, substance abuse, and depression spike drastically during the dark months. Northern Alaska has one of the highest suicide rates in the nations, specifically impacting their indigenous communities. This heavy, intense energy could be felt without actually being in direct contact with any of those unsavory side effects.”

I stop again at the sideview of a house, icicles lining the eaves, a car barely visible under mounds of snow. “I don’t remember where that magenta light was coming from,” Mahaney says, pointing at the snow blanketing the home’s roof, candy-like lavender in hue. “The colors of this place are bizarre. Normally, you wouldn’t notice the temperature of lights. But when it’s only nighttime, you begin to see all these different colors from artificial light sources.”

On the following page, the first sign of life is presented, the black silhouette of a dog against a chain-link fence, his features barely visible. “The cold was draining the battery so quickly that the strobe misfired on this picture.” He grins. “But I happen to like the misfire more than if this dog had been perfectly lit.” Pictures of dogs—the last sled dogs in Northern Alaska—appear several times throughout the book. They come across as ominous and menacing, especially in a photograph where two dogs bear their teeth as if poised to tear something—or someone—apart. “The dogs are a nod towards this idea of survival which appears throughout the book,” Mahaney explains. “For a while, we were going to call the book Three-Dog Night, which is a crude way of describing the temperature’s intensity on a given night. It means you would need three dogs in your tent to keep you from freezing to death overnight.” Allusions to survival and isolation are counterbalanced with a few moments of levity. A picture where someone has scrawled “good pussy” on a snow-covered door with an arrow pointing to a neighboring house receives an immediate and welcome laugh.

Various views from throughout the town follow until a striking picture of a young man, dressed in a wrestling uniform, postured as if ready to pounce, interrupts this flow. He is the only person in the book. “I left this town thinking that the project was these eerie, melancholic snowscapes juxtaposed with youthful, inspirational portraits of high school students,” Mahaney recalls. After seeing a team of teenage athletes on his incoming flight and speaking with their coach, the high school ended up being one of few places he was able to make portraits. But as he worked on the book with Bryan Schutmaat, Matthew Genitempo, and Cody Haltom—the team behind Trespasser Books who closely collaborated with Mahaney on the editing and sequencing process—he was convinced to take a different path. “Bryan was very adamant about cutting all the portraits except this one. I initially fought his suggestion, but I ultimately realized this was the right decision. This one portrait—like the dogs—injected this punctum into the sequence. I like that this is the town’s main athlete and he is in this warrior pose, preparing to survive the match.”

The Trespasser team also advocated for the final image in Polar Night, a photograph of Utqiagvik’s primary tourist destination, exquisitely lit as the sun rises on Mahaney’s final day in town. The jawbones of a bowhead whale—an important source of food for local, indigenous communities—arch high alongside a beached, traditional sealskin boat and a contemporary motorboat. Though there is a hopefulness to this serene scene as sunlight paints the sky in pinks and blues, there is also something melancholic, “something that points to the threatened culture of this place,” he says.

Also embedded within the fabric of the town and this work is evidence of the serious and complicated threat posed by climate change. Though Mahaney’s snow-laden landscapes do not immediately elicit thoughts of climate change, an unsettling report from 2017 suggests otherwise: the average air temperature recorded at a local monitoring station in November of that year was so high that the sophisticated computer software used by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) rejected the readings as flawed.[2] Due to its proximity to Prudhoe Bay Oil Field—the largest in North America occupied by companies employing many of Utqiagvik’s residents and paying dividends to native landowners through property taxes—the community has struck, as he puts it, “a Faustian bargain of sorts. The main revenue source is also impacting the decline and eventual disappearance of this place. The sea ice surrounding Utqiagvik used to be thick enough to protect the town. But it has now thinned to the point where waves crash and break through the ice, washing away a bit of the town every time. And what will this town do then when the oil fields eventually dry up?”

“I hope I gave you enough to work with,” Mahaney says as I close his now sold-out book. “I’m not used to talking about my own work because I haven’t done a personal project or book before. I could talk to you all day about the challenges and process of assignment work. I’m not used to all the choices I have with personal work. Given the town’s remoteness, the conditions at play with endless darkness—no beginning or end marking one day from the next and the impact on the rhythms of the body—not to mention the biting cold, I feel like I definitely chose a doozy for a first project.” Such clarity of vision and thoughtful editing demonstrate Mahaney’s sophisticated understanding of the medium, which will hopefully be brought to bear on many future personal projects given what we’ve seen in Polar Night, an exceptional debut monograph.

[1] Formerly known as Barrow, the town voted in October 2016 to restore its traditional Inupiaq name, Utqiagvik, which translates to “the place where snowy owls are hunted.”

[2] Henry Fountain, Brad Plumer and Hiroko Tabuchi, “Temperatures in Alaska Were So High That Computers Said ‘No Way,’” The New York Times, December 13, 2017 https://www.nytimes.com/2017/12/13/climate/climate-newsletter.html