Carolyn Drake’s Collaborative Project Internat

British Journal of Photography

March 2018

Carolyn Drake, from the book Internat © Carolyn Drake

Over a decade ago, artist Carolyn Drake first visited the Ukraine as part of a yearlong Fulbright fellowship to investigate changing notions of gender in the former Soviet Union. After coming of age at the end of the Cold War with specific preconceptions about the region, she recollects, “I saw it as a chance to step out of my present frame of reference, as a way to look at the malleability and impermanence of beliefs.”

As she searched for expressions of female identity in Western Ukraine, hosts at a church-run orphanage directed Drake to an older, nearby institution. Tucked away in the forest on the outskirts of Ternopil was the Internat, a state-run home where about seventy girls and women—ranging from 5 to 35 years of age—were sent to live because of reported illness or disability. For whatever reasons, the residents were deemed abnormal, unfit to live beyond the home’s towering walls. Drake recalls, “I remember a lot of children yearning for affection: tugging, pulling, and caressing. I remember nurses in white uniforms supervising classrooms, dark hallways, girls bouncing and swaying while the boom box blasted beats over the balcony. It was like the backstage arena for kids who didn’t make the cut for model Soviet child.” That first visit took place in 2006. Eight years later, she returned to the Internat, eager to find out what became of the girls she had encountered and the place where they had lived.

In the years between her first visit and subsequent return to the Ukraine, Drake completed two projects that deepened her interest in engaging communities and exploring the interactions within them: Two Rivers (2007–13) and Wild Pigeons (2007–14). In Two Rivers, she examined the expansive territory between the Amu Darya and Syr Darya rivers in central Asia, working with fringe communities in an area “where political allegiances, ethnic bonds, national borders, and physical geography [were] in constant flux.” Concurrently, she worked on Wild Pigeons, photographing the landscape and people in the remote, yet rapidly transforming territory of Xinjiang Uyghur in the west of China. Wild Pigeons incorporated an additional element of engagement with the community. Drake traveled around with her prints of the area and some art supplies, inviting those she encountered to draw on, collage, embroider, or reassemble the photographs. In so doing, she hoped these new images would integrate the Uyghur perspective into the work. “It allowed a different kind of interaction with them—one that was face-to-face and tactile, if mostly without words,” Drake recounts. “There was a kind of creativity in these different spaces that isn’t a part of everyday life.” These experiences informed her time in the Ukraine, helping to shape the approach for her most recent body of work, titled Internat.

When Drake returned to the Internat, she expected a changed landscape given the radical revolution that had wracked the country earlier in the year. She remembers, “I expected to show up and ask someone on the staff how to find the girls, but when I arrived, I found most of them were still there, now in their 20s…The place was set apart by the same concrete wall, the women grew cabbage and pulled weeds in the same summer garden, and they had the same stick mops to clean the floors. The most significant change I saw was that the girls had grown up.”

Over a two-year period, Drake photographed and worked with many of the women she had first met and photographed as children. Despite significant restrictions set by the home’s Director—she was only granted access to the hallway, patio, and one classroom, and was regularly prevented from making photographs—she found different ways of integrating unexpected play into otherwise uneventful daily routines. “I let my rational brain interfere more than I had before by bringing pre-conceived ideas to the shoots,” she writes. Although Drake came prepared with possible scenarios, this photographic process was more collaborative than in previous projects. “The ideas I arrived with became a lot more interesting once the women got involved and started transforming them, sometimes just by being themselves…We played at picture-making using their bodies and objects found around the building as content, and using this environment (where we were stuck) as a stage for imagining something beyond it.” The resulting photographs illustrate the surreal world these women crafted from their surroundings alongside the harsher reality of the stark environment. By so intimately including the women in her creative process, Drake felt she could “address issues I had with the power dynamic of classical documentary storytelling—who gets to tell whose story, and on whose behalf? I felt like this blending of authorship gave the work more depth.”

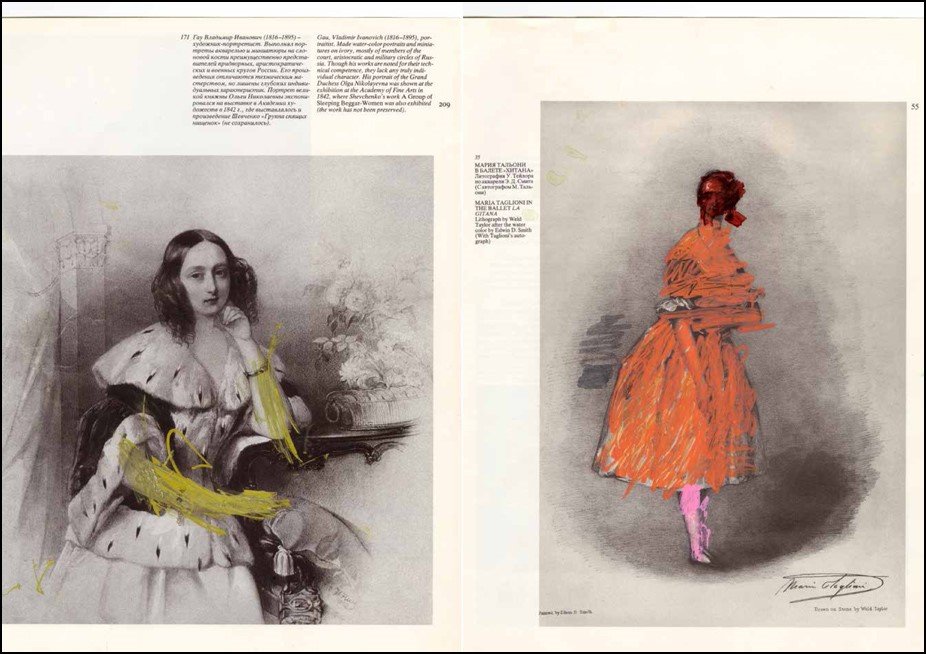

This blended authorship translates into the book design for Internat. On the cover, instead of a photograph, we find a crudely painted illustration of an enigmatic woman, eyes downcast, seemingly not of this time. The photographs in Internat are bookended by similarly altered images. Drake asked the women to paint over pages from The Artist, a book about the life and influences of the now widely revered nineteenth-century Ukrainian artist, ethnographer, serf, peasant, and poet, Taras Shevchenko. “Shevchenko fought for the empowerment of the peasant/serf and their release from captivity under Russian imperial rule,” she tells. “I liked the idea of considering this celebrated historical male figure—an imprisoned serf—in relation to these contemporary women of the Internat, also serfs in a sense, but captive and overlooked.” Through an empowering gesture of revision, the women rework classical images—many of which are folkloric or mythological, a clever reiteration of the fairytale sensibility permeating the photographs—illuminating, scratching out, and transforming the content of the images. Prominent integration of these personalized artworks strengthens the notion that collaboration lies at the project’s core.

Drake’s sophisticated edit augments the intrinsic tension between reality and fantasy in the photographs. In thoughtfully intermingling collaborative portraits, candid moments, cryptic still lives, and somber landscapes, she creates a world where the occult and everyday comfortably coexist. Sparks of creativity and profound expressions of sisterhood are offset by melancholic allusions to control, solitude, and confinement. Internat teeters on the edge of narrative, cultivating an ambiguity that challenges the viewer to reflect, rather than rush by.

The photographs are traditionally presented in the book—usually featuring a single image per spread—a decision Drake deliberately made in light of the work’s content. “Since the pictures themselves had their own peculiarity and confusion,” she says, “I wanted to keep the design straightforward.” While the image layout is more conventional, the book itself is not. Drake explains, “I also wanted each book to be individualized somehow, or to rest in an area between uniformity and individuality, as many of the pictures do. So we came up with this idea of allowing the cover to open up to reveal a spine that is both covered and exposed by a hand-colored cloth. I see this open cover as a reference to the wall that appears over and over again in the background of the images. The images themselves also play with revealing and obscuring.” Her sensitivity to materials and to the relationship between content and form elevates Internat from book to art object.

Together with her two earlier projects, Internat underscores Drake’s unwavering interest in “the barriers and connections between people, between places, between photographer and subject, between ways of perceiving.” Her poetic approach to marginalized communities—subject matter typically associated with photojournalism—subverts expectations. Through her collaborative process, she gives a voice to people who might otherwise remain unheard.